Introduction and Summary

According to an article entitled “ESG Funds Draw SEC Scrutiny” that appeared in the Wall Street Journal on December 16, 2019, regulators at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) are scrutinizing some investment management firms that market themselves on the basis of socially responsible considerations or the adoption of strategies involving the integration of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors, such as climate change and corporate diversity. Initiated out of the SEC’s Los Angeles office, the article goes on to report that the SEC has focused on the criteria used by managers for determining whether an investment qualifies to be socially responsible, their methodology for applying those criteria and making investments. This comes at a time during which the number of sustainable investment products being offered in the US to retail and institutional investors and their corresponding strategies have grown substantially, assets have ballooned, and claims by some firms may be leading investors to expect unrealistic outcomes as to societal impacts and/or the potential for outperformance. The absence of universally accepted definitions and methodologies is contributing to a widening range of confusion and misunderstanding around sustainable investing practices and expectations/outcomes. To head off potential disappointment on the part of investor clients of all types and avoid asset manager exposure to potential reputation risk, regulations and worse, financial liabilities, voluntary sustainable investment frameworks and increased disclosures should be undertaken by the investment company industry.

SEC concerns: ESG has no enforceable or common meaning

Senior SEC officials have sometimes expressed concern that focusing too narrowly on corporate morality could undermine a money manager’s duty to act in the best interests of clients. That could become a problem for pension funds pursuing ESG strategies if their retirees and beneficiaries aren’t as interested in sustainability but are nevertheless locked into funds’ investment choices, Republican SEC Commissioner Hester Peirce said last year. Ms. Peirce has criticized ESG for having no enforceable or common meaning. In a speech last year to California State University Fullerton’s Center for Corporate Reporting and Governance, she noted that “While financial reporting benefits from uniform standards developed over centuries, many ESG factors rely on research that is far from settled.”

While their focus on aspects of sustainable investing varied, the subject has attracted the attention of governmental bodies beyond the SEC. In July of this year, the US House Financial Services Committee held a hearing on the topic of public company ESG disclosures. A few month earlier in April, the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs held a hearing on the application of ESG principles in investing. Also in April, the Trump Administration directed the Department of Labor in the form of an executive order to conduct a review of the discernable trends in qualified retirement plans subject to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) with respect to investments in the energy sector and proxy voting practices in light of fiduciary responsibility guidelines.

Funds and assets linked to sustainable strategies have expanded dramatically, especially in the last five years

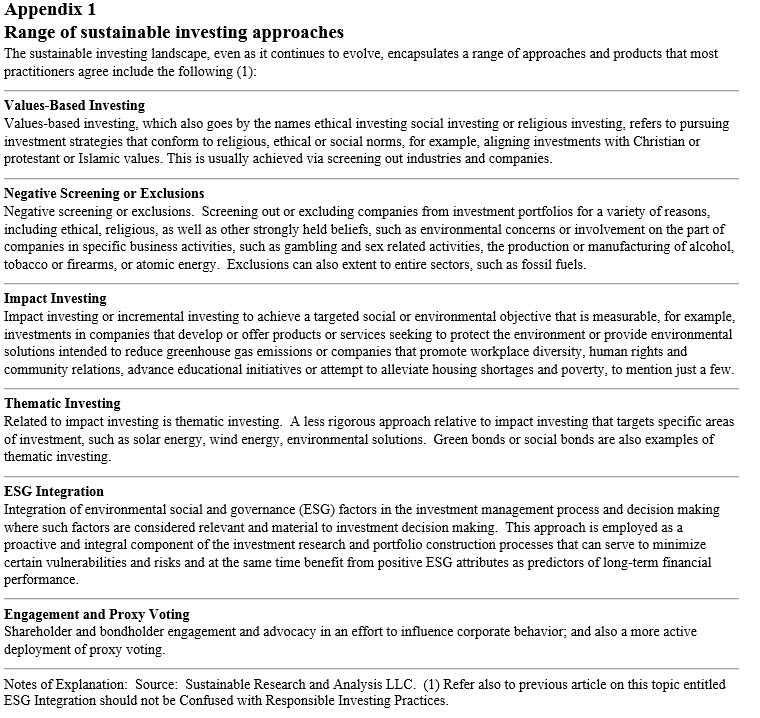

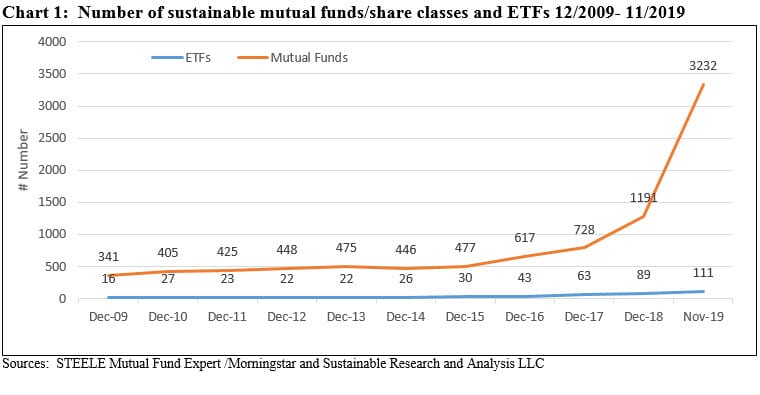

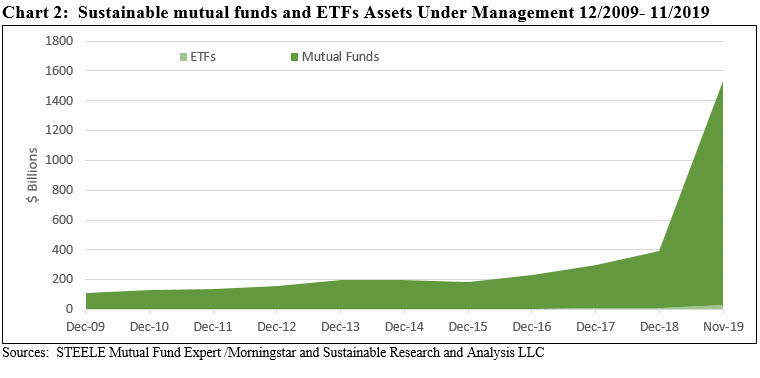

Sustainable assets under management in mutual funds and ETFs have expanded significantly in the last decade and are deployed across a variety of sustainable investing approaches ranging from values-based socially responsible investing and negative screening or exclusions to impact and thematic investing, ESG integration, engagement and proxy voting. Refer to Appendix 1. These are offered today by 154 separate firms via upwards of 3,300 mutual funds/share classes and ETFs, up from 357 funds/share classes at the start of the decade and just 59 firms. Refer to Chart 1. That said, much of the growth in recent years is attributable to fund re-brandings (by formally adopting sustainable investing enabling language in fund prospectuses) and market appreciation rather than net new money which has been identified as a particular area of concern to the SEC. Between the end of 2016 and November 2019, a period of almost two-years, sustainable assets under management increased by almost $1.3 trillion, from $233.5 billion to $1.5 trillion. Of this increase, 92% is attributable to fund re-brandings. In the process, ESG integration has overtaken other sustainable investing approaches. For example, an analysis of the top 20 sustainable investing firms based on assets under management that account for 92% of assets at the end of November 2019 shows that ESG integration, either exclusively or in combination with other sustainable strategies, is now the dominant approach. Also leading to confusion, however, some firms avoid making a firm commitment to adopt ESG integration but rather disclose that they may employ ESG factors.

Sustainable investing generally has been gaining traction for a variety of reasons, the most significant being a growing awareness about climate risks following the Paris Climate Agreement at the end of 2015 (COP 21). Since that date, assets sourced to sustainable strategies have increased by an average of 94.3% per year to reach $1.5 trillion versus an average 9.1% annual gain to reach $185.8 billion in the five years between the start of 2010 and the end of 2015. Refer to Chart 2. Not in any particular order, other contributing factors include worrisome societal trends such as gender and income inequality, gun violence, water scarcity, poverty, migration, education and a deterioration in corporate governance standards that many believe contributed to the 2007-2008 financial crisis. Prompted by governments, regulators, businesses and investors, the recent evolution in sustainable investing is informed by the view that the achievement of positive societal outcomes via sustainable finance is consistent with long-term value creation. That is to say, doing well financially is compatible with doing good.

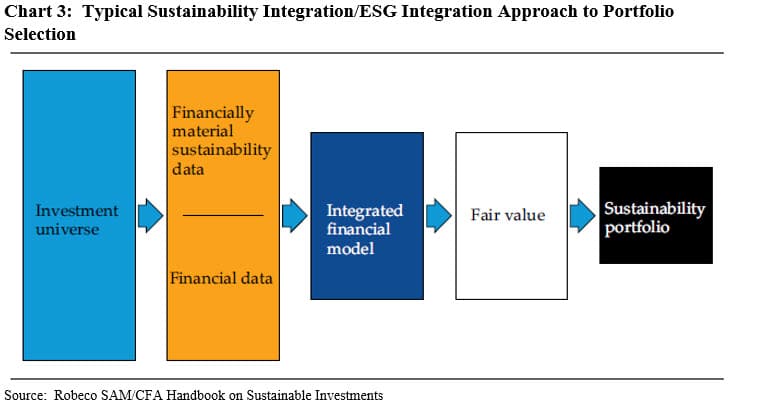

ESG integration has paved the way for the widespread adoption of this view. Whereas values-based investing has historically been associated with underperformance, ESG integration as a strategy has been fueled by research studies that have shown a correlation between sustainability measures in corporations and financial performance, such as improved cash flows, lower cost of capital and higher valuations. According to the CFA Institute, ESG integration refers to the systematic and consistent accounting of relevant and material ESG factors in investment decisions. Examples of ESG factors include natural resource use and scarcity, governance controls, product safety, employee health and safety practices, and shareholder rights issues. Investment managers who have adopted ESG strategies believe these issues should be considered alongside traditional financial measures to provide a more comprehensive view of the value, risk and return potential of an investment. Refer to Chart 3. In many instances, these considerations were already accounted for in investment decisions, but the adoption of an ESG lens introduces a systematic and consistent basis for doing so across companies, sectors, geographies and security types.

Other drivers that have supercharged the uptake in ESG include risk management, client demand, regulations, especially in Europe, and fiduciary responsibility. At the same time, investors are attracted to sustainable investments on the basis that these can coexist with performance considerations even as there is no conclusive evidence in the literature that sustainable funds consistently outperform or underperform conventional funds. In fact, the lack of standards and a short track record impedes the conduct formal fund performance studies.

Commonly accepted definition of ESG integration does not exist today

Still, a commonly accepted definition of ESG integration does not exist today and asset owners, asset managers, issuers, retail investors, regulators and various other market practitioners are not synchronized regarding what the strategy means, what are the relevant and material considerations and inputs across varying asset classes, securities, security types, sectors or geographies to mention just a few, how to apply ESG factors, and what are the expected financial and non-financial outcomes. One consequence of this is that there is confusion between varying strategies and approaches that make up the sustainable investing landscape, in particular by conflating ESG funds or ESG integration and values-based investing and negative screening or exclusionary approaches. This muddying up of two unlike sustainable investing approaches has also crept into the day-to-day conversation and unless checked, is likely to deter investors, in particular individual investors, lead to disappointment on the part of clients of all types, and expose asset managers to potential reputation risk, regulations and worse, financial liabilities

Regardless of approach, disclosures are key

It should also be noted that sustainable investing approaches are not mutually exclusive and some managers combine one of more methods. Regardless of the approach or products offered, however, it is key for investment management firms to offer investors who are attracted to sustainable investing a clear explanation of their approach and strategies, how such strategies are implemented, their impact on investment decision making and outcomes, both from a financial return point of view and, to the extent possible, in terms of social, environmental and governance outcomes. The same applies to all financial and related fund reports. Solidifying such disclosures, however, would be an effort to develop an industry-wide taxonomy consisting of terms and definitions.